An interview with wealth psychologist James Grubman, Ph.D.

Dr. Jim Grubman has spent his career studying the impact of wealth on families, especially new wealth, and what differentiates those who successfully adapt to their new lives. By approaching the topic through a psychologist's lens, Dr. Grubman has uncovered important insights into how first-generation wealth creators can navigate what amounts to a surprisingly novel culture.

His book, Strangers in Paradise, reveals that families who come into wealth have experiences akin to immigrants in a new country. The decisions they make about their values, their behaviors and, perhaps most importantly, how they raise their children inform how effectively they may integrate their new fortune into the future of the family. Their choices also impact whether the family's financial capital supports or undermines growth and development and whether that wealth will last for generations.

First Republic had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Grubman about his work. We especially sought his best advice for how parents new to wealth can help their children succeed in an economic culture very different from the one the parents experienced growing up.

What initially intrigued you about this topic — and why do you think it’s an important one to address?

Traditionally, we’ve mostly talked about wealth in terms of class. But I came to realize that becoming wealthy is more about a cultural shift — a perspective that really hadn't been discussed much. Society often thinks of “the rich” as one amorphous group with few distinctions. At the most, we might talk about old money, focused on inheritors, and new money or the “nouveau riche.” But those generalities don’t capture the complex experience of the wealthy and their many subtypes.

Studies consistently show that, in the United States and most other countries, around 80% of the rich achieved their wealth in their lifetimes. It’s mostly new money, decade after decade. But there’s a problem. With so many people coming in, the proverbial “land of wealth” should fill up with the descendants of those people — there should be increasingly more inheritors than the small minority that actually exists. The answer is that the proportion stays the same because people must be leaving the land of wealth at a faster rate than people are entering it.

So, I started looking at why that is. What I discovered is that it’s not about the money. It’s about the unexpected challenge of adapting to the new life. People are surprisingly unprepared to be rich in terms of adapting to a new culture. It presents all sorts of new issues for the family, most especially for parents.

Can you explain more about how the wealth transition experience is both cultural as well as economic?

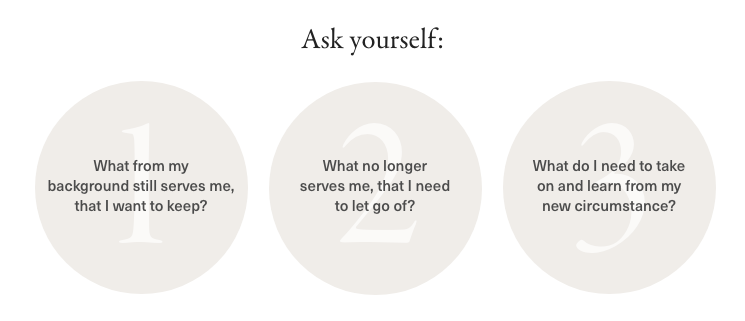

Strangers in Paradise looks at wealth transitions from a cross-cultural, psychological perspective. The experience of wealth is overwhelmingly one of people who came from someplace else, economically. They are genuinely immigrants to a new culture. If you're raised middle class, you carry forward attitudes, ideas, habits and views about money and wealth that fit with what you once knew — but may not apply in the new culture. Immigrants to wealth need to ask themselves the same three questions immigrants to new countries face: What from my background still serves us well, that I want to keep? What no longer serves us, that I need to let go of? And, perhaps most importantly, what from my new circumstances do I need to take on and learn?

A very affluent couple I once worked with offers a good example. The marriage was economically diverse: the wife grew up with money, and the husband was working class. They were at an impasse about buying their 16-year-old son his first car. The wife was in favor because of her own experience, but the husband said, no way! He had ridden the bus when he was young because that’s all they could afford. He still thought it helped him build character by exposing him to different people and forcing him to work and save up money. When he finally bought his first car, he truly appreciated it and made sure he took care of it.

In talking with them, I drew out the underlying values and skills the husband had learned from his experience, such as self-sufficiency, humility, gratitude and enduring respect for people in other economic classes. These are the things from his previous economic culture he wanted to instill, as did his wife. So, the question shifted to: How can the son, living now in a very different environment, learn the same skills and values without necessarily going through the same process? That was the adaptation part. They easily agreed the son should earn half the cost of a vehicle, and it wouldn't be brand new, so he would need to learn how to maintain it. It was a win-win. In the end, the husband learned to let go of how he obtained his life lessons while still keeping those valuable skills and goals for his children.

As wealth’s immigrants navigate these parenting dilemmas, what are some of their biggest concerns for their children?

Good parents don’t want financial security to get in the way of raising motivated, grounded and capable children. One risk is that money can siphon away or cushion opportunities for children to experience frustration. People need to experience adversity and challenges on the road to building character.

What commonly stumps parents new to wealth is how to handle saying “we won’t” versus “we can't.” In middle-class life, when you can’t afford something your kids ask for, saying “we can’t” is the right reply. But when money is no longer an issue, saying no isn’t so easy. Unless you plan to cave to all requests, your choices are to either skirt the truth or come up with a better answer. Neither is easy.

Realistically, many well-off parents think “we can’t” remains a perfectly fine response. They feel that if their children believe money is limited, they'll be better for it. After all, that’s how the parents learned money skills themselves. But eventually, parents will have to reveal the truth, either in person or through their estate planning. It’s surprisingly hard. Some adult children may be upset at the deception, questioning why the parents withheld information or didn’t trust them with an honest answer.

Those parents willing to adapt learn that saying no is not just about scarcity, it’s about values. The answer becomes: we can buy that, but we won’t. We have the money, but here’s why I’m not going to buy that. You have to talk about the rationale for purchasing decisions. In the end, that’s healthier for kids to learn.

How can wealthy parents effectively handle issues of money at different stages for their kids?

Parents can do some practical things in their kids’ early years, such as teaching manners. Kids with good manners understand respecting others, being kind and showing gratitude. An allowance is also key. It’s the best vehicle for first learning money skills, the prelude to wealth skills. You generally want to be able to talk with your kids about money in a relaxed way and convey good money messages that signal your values.

In middle and high school, it’s important to develop initiative and the capacity to delay gratification, fundamentals for good spending choices. By then, kids should be learning to navigate more complex decisions. As they become young adults, it’s about finding purpose and demonstrating a good work ethic, even if they have access to trust income or family assets. Natives of the land of wealth still need to pursue a career or interest with diligence — purpose gives value to life and character.

Beyond the ages and stages, what are some good practices for wealthy families in general?

Conventional wisdom believes “the rich” never talk about money, but that couldn't be farther from the truth. Experienced affluent families have a remarkable openness around money discussions and financial education. Whether families are new to wealth or in their fourth generation, communication is the secret sauce for success.

A prime way to do that is through regular family meetings. These are formal or informal times reserved for talking about the business of the family. You have to offset the tendency for money to become invisible and taken for granted. Meetings bring it back to the forefront and ensure that parents and children are comfortable discussing money issues. For instance, with younger kids, you might discuss how the allowance is going or what the family wants to do for an upcoming vacation — great opportunities to teach budgeting and planning. As kids get older, you can start to introduce more complex topics and gradually disclose more about the family’s money management.

For families you work with, what is the ultimate goal in terms of wealth transition and education?

When it comes to parenting, your primary goal is to prepare children to be good decision-makers in the many roles and responsibilities they will have in life. This means modeling good decision-making when you can while allowing children to learn for themselves, even with mistakes. Don’t be too shy about sharing your own painful but valuable money lessons; kids will take comfort in those stories when they inevitably have their own setbacks. By adulthood, children should know how money works, how life works and how to navigate the hard choices that life requires.

Ironically, the bottom line is for the whole family to be able to put money in its place. When you grow up without money, money takes on outsized importance and power. As parents, our goal is to develop strong, capable people who are equal to the power that we grant wealth. That’s what success truly looks like.

This information is governed by our Terms and Conditions of Use.